Created at: 2024-08-06

The ecosystem for managing Python environments is huge, and so is the number of tools that are used to manage these environments.

We have: pyenv, virtualenv, virtualenvwrapper, asdf, conda, anaconda, uv, poetry, pipenv etc.

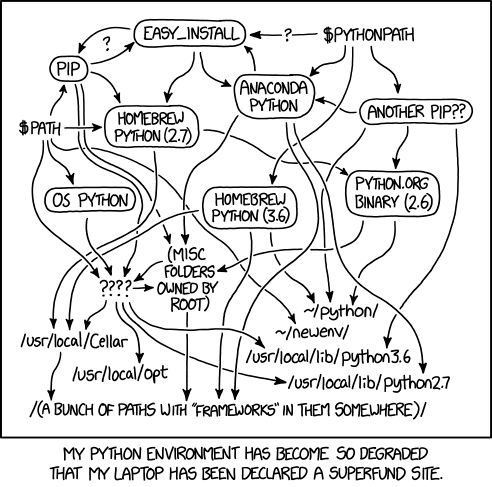

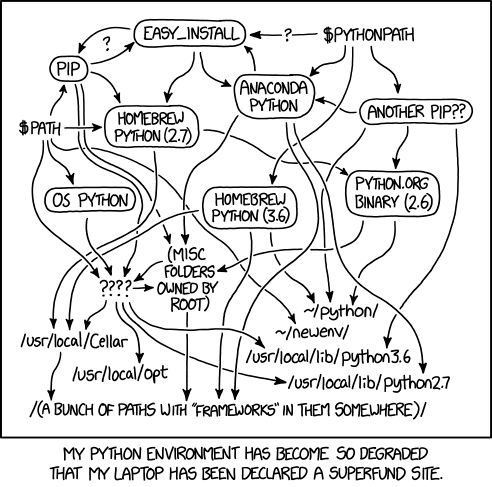

It is very easy to break your local environment if you are new to all of this. This cartoon from xkcd sums it up well:

The purpose of this post is to argue whether we need any of these tools when working on multiple Python projects that potentially have incompatible Python versions and dependencies.

Mind you that I program for work. Some of the knowledge and intentions behind the way I do things have been learned through trial and error over time. What is written here assumes that you either have a similar background or the ability to understand or come to common ground on why some of those decisions are harder to me than others.

Also, I expect that you don't need convincing that using your global Python executable for everything is a bad idea, and that isolated virtual environments for each project is the best solution to avoid dependency headaches.

Every tool I cited above is a little bit different, but I will pick pyenv as an example since it is one of the tools with the smallest footprint.

pyenv let's you:

pyenv install 3.10.4cd into a folder: pyenv local virtualenv among other tools.This all sounds pretty neat, but is it worth installing this tool made of 101,263 lines of code and data files (as per v2.4.9) just so that you have these commands plus a plugin framework?

My answer is no. You are not going to need it and you are better off with the default tools (more on that later).

There're three main points that I consider undesired behaviour coming from the abstraction provided by pyenv:

pyenv collection of shims at the beginning of your $PATH variable, as in: $(pyenv root)/shims:/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin`

pip so that the correct virtualised pip version for the directory you previously cd into is chosen. Effectively, these shim commands replace your Python environment commands like pip by the commands hardcoded by pyenv that do the magic for you. But besides the magic nature of those shims, they can be very slow (example). If you have many Python projects, these shims start to become a bit of a dark magic and you won't have direct access to the Python tools if anything bad happens. Plus if pyenv adds an order of magnitude of slowness as compared to running the Python binary itself, pyenv becomes a painful tool to use.pyenv itself. Checking for recent issues in the repository, one can see many distinct problems ranging from incompatible changes within pyenv itself, to weird missing C++ links in the Python executable, failing to create a virtual environment for a specific version of Python, unavailable or unsupported Python binary, operating system upgrades breaking the tool, etc. There are 1,700+ issues to date to pick from.After reading all that, you might still find that pyenv is actually useful for you and the drawbacks aren't that meaningful. If that is the case, please go for it! If pyenv wasn't useful it wouldn't be so popular. But developers come in different flavours, and given past experience I can tell that pyenv isn't for me.

I personally am not a big fan of magical tools and I like to have control and understanding of how to fundamentally control my work environment as this is an important part of my job. Any breakage in my local environment in the past has caused me great pain and stress. Most of these problems have been caused by mismanagement of dependencies; problems either created by me (lack of knowledge of how underlying tools work), by the Operating System (ubuntu and MacOS in particular), or by magic tools changing in backwards incompatible ways.

On the other hand, I have frequently been surprised by how easy it is to learn and use basic tools available by the OS or the programming language itself, which has only added to my scepticism of magical tools adding value in exchange for their added cognitive load and potential bugs.

I also mentioned at the top of this section that pyenv is one of the tools with the smallest footprint. That is true. Other tools such as conda, asdf and, heck, nix are on a higher level of abstraction. To me, they are even less desirable for the task of managing Python environments locally.

There are also other caveats with these tools such as the fact that they change, grow bigger, and sometimes these changes create backwards incompatibility with their own earlier versions as we saw above with pyenv.

It is not hard to find issues on those repositories where some conflicting dependency has broken the dependency resolver tool itself 1]. If you are in a situation where you need a version management tool to manage your version management tool, things get complicated. It is a fact that software breaks, and if your environment management that is build upon high levels of abstraction has failed you, how will you fix this issue without knowing enough about this 100,000 lines code repository?

I can only speculate on empirical knowledge since I don't have any hard data I can reach to, so take that with a grain of salt.

I imagine that whether someone will choose to use an environment manager tool comes down to their background. Preferring to pick a tool over another is a choice compounded by many factors:

I am writing this article in 2024. Building Python from source is incredibly easy yet surprisingly very few people actually do it. Yes... Building from source! What a crazy idea, nobody builds from source these days and many people don't know how to.

It is possible to download a specific Python version and set up a virtual environment using Python's own venv tool without any extra dependency whatsoever.

Here's a short list of bash commands that download Python 3.11.5 and set a virtual environment for it:

# You'll be installing your Python binaries at $HOME/python_bin.

mkdir -p $HOME/.python_bin/ && cd $HOME/.python_bin/

# Download the tar for the Python version you want.

curl -O https://www.python.org/ftp/python/3.11.5/Python-3.11.5.tgz

# Decompress and install it.

tar -xzf Python-3.11.5.tgz && cd Python-3.11.5

./configure --prefix=/tmp/localpython/3.11.5 && make && make install

# Create your environment anywhere you like.

./$HOME/python_bin/Python-3.11.5/python -m venv my_env

source my_env/bin/activate

That is it. Now you know how the whole process works (it is so easy) and you're using venv which was introduced to core Python in 3.3+. You can also play with compilation flags and build the binary with some extensions (but you don't have to!).

Of course this is still using some tools that abstract the burden of building the binary for the project. If you have never built a big C project like CPython before, you might be asking yourself what is this ./configure script, what is make and so on so forth. In a nutshell, this is how binaries are usually packaged - at some level either you are doing this or your operating system has come up with a standardised way to build from source for you via a package manager.

So now you can run however many virtual environments you want from that binary, and put them anywhere you like. If you want extra convenience to activate that environment for a particular project, just create an alias:

alias myproj="/somewhere/my_env/bin/activate && cd /somewhere/myproj"

If you aren't using Python 3.3+, just swap venv for anything else that works for your version, or heck, just directly use that Python executable for your project - it is totally disposable and you can download another one any time you like. Now that you know how the process works, it is very easy to change it to your taste, and that's exactly what I wanted to show in this post.

If you want some further ideas, this is the script I am using on my bashrc file.

install_python_version() {

# call this function with a version of Python

# like `install_python_version 3.11.9`.

# Clean up first

rm -rf /tmp/python-install

# This is where the different Python executables will be installed.

DIR=$HOME/.python_bin/python-$1

mkdir -p $DIR

# This is where temporary installation files will be available.

mkdir -p /tmp/python-install && cd /tmp/python-install

# Download the python version

curl -O https://www.python.org/ftp/python/$1/Python-$1.tgz

tar -xzf Python-$1.tgz && cd /tmp/python-install/Python-$1

./configure --prefix=$DIR && make && make install

echo "Now you can install your virtualenv:"

echo "$HOME/.python_bin/python-$1/bin/python3 -m venv /tmp/my_env"

}

You can invoke it from the shell with install_python_version 3.11.5.

While this is generally true, and package managers are incredibly useful tools, I think that it is worth picking a battle now and then and building something from source when it makes sense to do so. I think that at a minimum, being comfortable building your main tools plus other tools that are notorious for having conflicting versions from source is a good general advice.

In my case, I rely on my OS package manager a lot for my secondary tools. But even though pacman is a great package manager, it is not without its drawbacks. It only builds dependencies with the default flags. If I need more customisation, I have to step out of the manager or understand how the manager works so that I can apply the particular building flags I want.

This is also a problem in a rolling release system like Arch Linux, as installing multiple versions of the same dependency will point you towards some form of virtualisation (using docker, for example) or building from source.